3D anatomy model - L'écorché combattant

An exciting update is coming! Soon, the Anatomy for Sculptors home page will feature a helpful new aid for artists – the 3D viewer! The same as the Human Proportions Calculator, which is already accessible on the website, the 3D viewer will also be available for free.

We will go over its multiple features in another blog post closer to the upcoming release. But while we wait, we will introduce you to one exciting model that will be available on the 3D viewer – an écorché by Jacques-Eugène Caudron called L’écorché combattant.

3D anatomy model made by the Anatomy for Sculptors team – L'écorché combattant

An enhanced 3D model of L’écorché combattant by Jacques-Eugène Caudron.

The unique posture of Caudron’s L’écorché combattant makes it an excellent aid in anatomy studies for artists. In this écorché you can observe muscles flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, supination, pronation, etc. Even the figure’s torso is in motion, with one of its sides bent and the other one extended.

First, we will share the story of a plaster figurine of Caudron’s L’écorché combattant that we found in the RSU Anatomy Museum in Riga and tell you more about the process of creating its digital model. Then, we will look at the modifications we have made to L’écorché combattant in our digital 3D model.

To read more about what écorchés are, explore their history, and learn more about what makes Caudron’s L’écorché combattant so special – check out this article!

L’écorché combattant in the RSU Anatomy Museum in Riga.

Écorché – made digital

An écorché is an excellent tool for artists in their studies, and Uldis Zarins, the author of the Anatomy for Sculptors book series, had often thought about making his own digital 3D écorché model. The benefit of scanning an écorché and recreating it digitally is that the digital model can then be measured using modeling software. This allows us to identify the original model’s anatomical mistakes and correct them.

Some fixed-up 3D models of écorchés for artists already exist. One example is the Eaton Houdon Écorché by Michael Defeo, a contemporary anatomical figure based on the classic L’Écorché, the 18th-century anatomy study by French neoclassical sculptor neoclassical sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon.

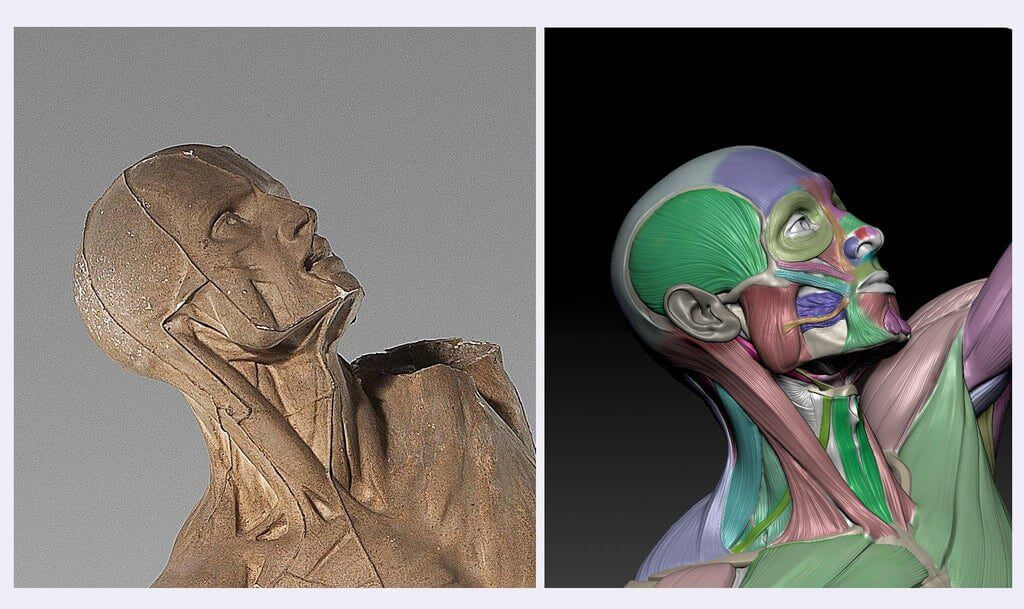

Torso of L’écorché combattant – the digital model beside the original plaster cast.

The keyword here is neoclassical – the sculpture follows strict canons and its form is highly influenced by the aesthetic standards of the neoclassical style. Although the Houdon’s écorché is widely known and used by artists worldwide, it is not the most informative écorché, mainly because its pose is very static and does not show much variety in muscle tension.

Muscle motion is varied in L'écorché combattant

Earlier this year, Uldis stumbled upon a small plaster cast of an écorché in the RSU Anatomy Museum in Riga – L’écorché combattant by the French sculptor Jacques-Eugène Caudron. This écorché differs from others because of its varied muscle motion. It is surprisingly animated, anatomically accurate, and illustrative. This extraordinary find inspired Uldis to pursue his idea of creating a digital écorché.

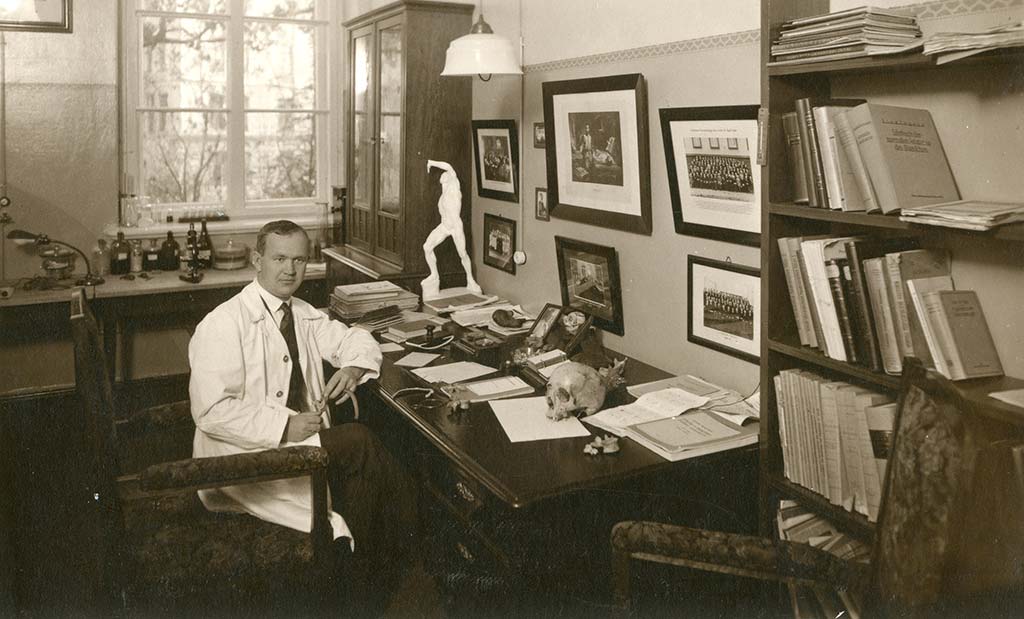

Professor Jēkabs Prīmanis in his cabinet at the Institute of Anatomy in Riga, 1929.

In cooperation with the RSU Anatomy Museum, the L’écorché combattant was scanned, creating a digital primary mesh of the sculpture that was ready for measuring, examining, and transformation. We will go into the details of the process and the changes made at the end of this article.

Ecorche 3D anatomy model – corrections and additions

Our ecorche 3D model has had some corrections and additions. Once we acquired the freshly scanned mesh of L’écorché combattant, we examined the basic geometry of the sculpture. We analyzed the inner symmetry of the pelvis and thorax and checked their alignment with the central axis of the body. To do that precisely, we embedded an anatomically correct skeleton inside the mesh.

The mesh of L’écorché combattant with a skeleton embedded in it.

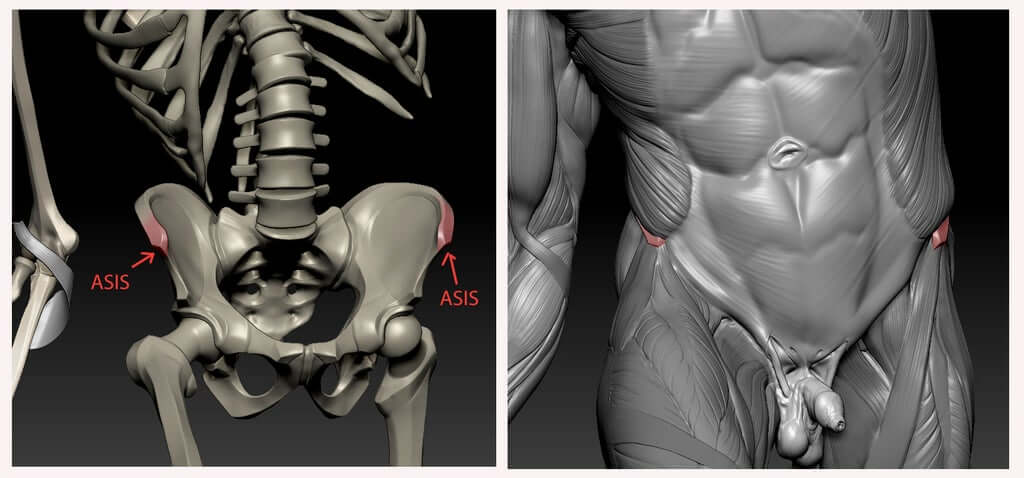

This led to corrections in the positioning of the pelvis along the bony landmarks of the body such ASIS and PSIS. Even though some corrections were necessary, it was surprising to see such high anatomical precision in a sculpture of such a small size given that all the measurements at that time were made with a caliper.

Another discovery was that the proportions of the écorché had been slightly adapted to suit the composition. The thorax had been pulled a bit closer to the pelvis than necessary, and the left arm was a bit longer than the right arm.

When the basic geometry was fixed, it was time for detailing the muscles. The first task was to check whether the muscles still fit the changed landmarks of the basic geometry, move them, and then fix their borderlines.

PSIS and ASIS pelvis shifts

The shifting of the ASIS changed the following muscles: Sartorius, Tensor fascia latae, and Rectus femoris. The correction of PSIS demanded changes in Latissimus dorsi and Gluteus maximus origins.

The muscles around ASIS in the 3D digital model of L’écorché combattant.

With the basic geometry and the muscles taken care of, it was time to look at the result and compare it to real-life anatomy examples. Our team compared the anatomy of the 3D model to radiological data from CTs, CTAs, MRIs as well as pictures from cadaver dissections. This work only confirmed the accuracy of the original écorché commissioned by doctor Fau.

Head and neck muscles added

However, we did make some additions to the original figures’ anatomy. Possibly the most notable in Caudron’s original is the absence of some of the head and neck muscles. We detailed them by adding the LLSAN, Muscles of the nasal and glabella regions, Buccinator, and Risorius.

Anatomy of eye and surrounding areas

We also fixed the eye area with a new pair of eyeballs and adjusted corners of the eyes. The aesthetical tradition at the time demanded that the mouth of the sculpture stays open. To avoid the need to detail the oral cavity (and in Uldis’ opinion to also reduce the creepiness level), the mouth has been shut.

Caudron also modeled his écorché without one ear to better illustrate the connection of the head to the neck. In our version after almost two centuries, we have given the poor man his ear back.

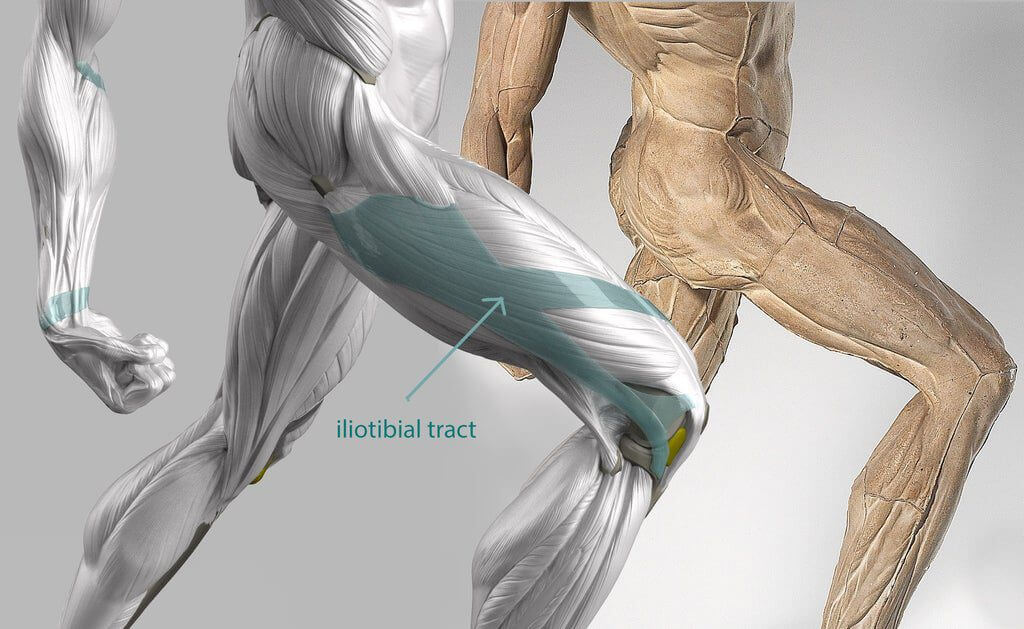

Iliotibial tract band

Another major addition to the model is connective tissue, most notably the Iliotibial tract and Bicipital tendon. Some connective tissue has also been added to the feet. Fingers and toes have also become more detailed.

Pelvic floor anatomy

Neoclassicism, the main art style at the time, tries to exclude or reduce all the so-called “primitive subjects” from the artworks – this includes all the elements of the body related to reproduction. In the case of L’écorché combattant, the penis in the sculpture is depicted as unrealistically small. In our 3D model, we enlarged it to make it more realistic. We also added the pelvic floor and the anus to the model.

Muscle color code for productive studies

The final step was to color-code the muscular system, including many of the smaller muscles that were not visible in the original sculpture. We have also made a separate removable mesh for the connective tissue to increase the flexibility of this 3D model when it is used in anatomy studies.

Watch our video series about écorchés to learn more!

In the first video, Uldis Zarins explains how écorchés sit somewhere between art and medicine. During the Renaissance the first écorchés were used mostly by artists, but later they also became increasingly popular among medical students.

Join our newsletter

Be the first to receive news about upcoming books, projects, events and discounts!