Ecorche – muscle and motion

In this article we will explore a short history of the ecorche as a phenomenon in art. First, we will shortly explain what an écorché is. Afterwards, we will explore the uniqueness of L’écorché combattant among other écorchés of the 18th and 19th centuries. This is a story of a static figure becoming a powerful demonstration of the link between muscle and motion.

Read about our discovery of a plaster figurine of Caudron’s L’écorché combattant in the Museum of the History of Medicine in Riga and the process of creating its digital model in this blog article! It also features visualizations of all the modifications we have made to Caudron’s sculpture in our digital 3D model.

Short history of Écorché

The back of a 3D model of L’écorché combattant by Jacques-Eugène Caudron.

What is an écorché?

The French word écorché means skinned. In art, the word describes an artwork in which the human body (or in some cases an animal) is depicted without skin and fat to illustrate the muscles.

The skinned figure, usually in the form of a plaster cast, wax, or marble sculpture, allows studying the arrangement and shape of muscles, veins, and joints. While there are écorchés of animals, particularly of skinned horses, the great majority of écorchés are depictions of the human male figure.

Collaboration between doctors and artists

An écorché was often the result of a collaboration between doctors and artists. The figures are usually shown in animated poses to express muscle tension and include decorative elements such as columns, plinths, and pedestals.

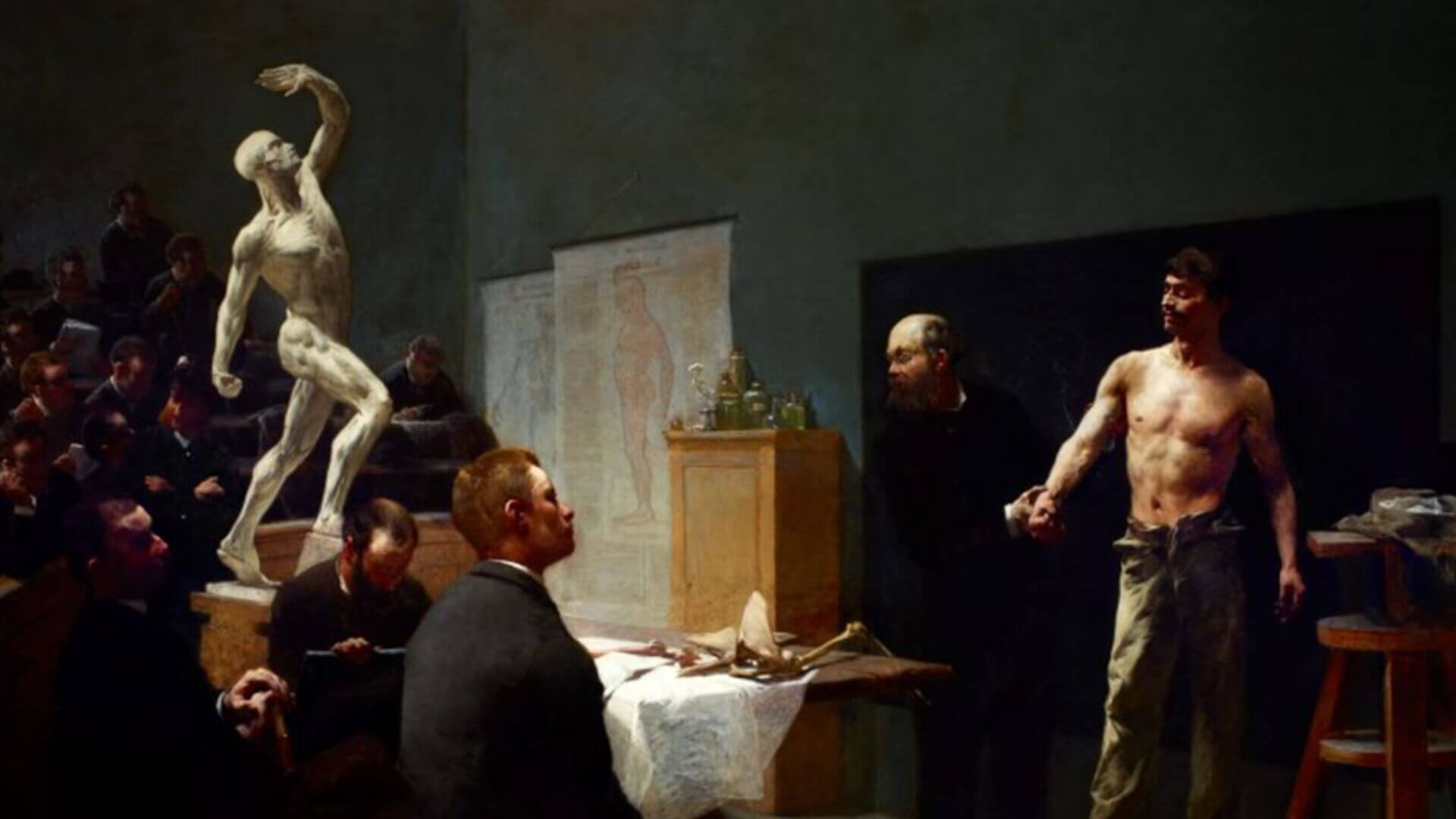

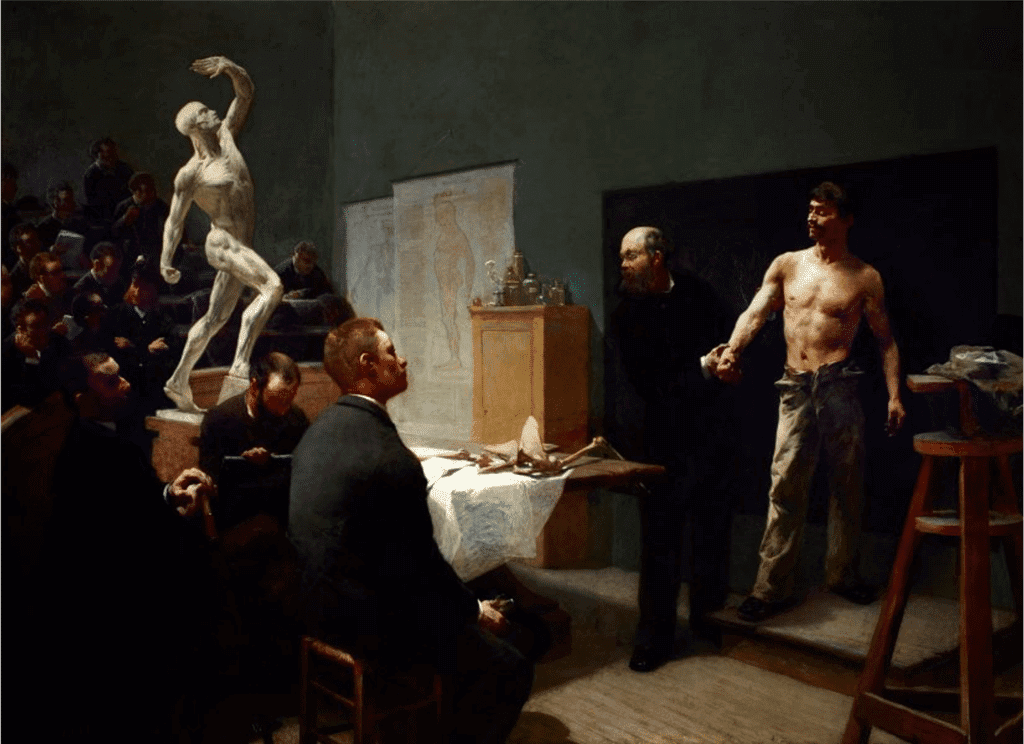

The anatomy class at the École des Beaux Arts by François Sallé, 1888 – L’écorché combattant visible on the left side of the painting.

The first écorchés

The first écorchés appeared in the Renaissance period, essentially as drawings and chalk sketches made by authors like Michelangelo and Leonardo Da Vinci.

However, the popularity and widespread use of these anatomical figures came later – at the end of the 18th and throughout the 19th century. In this period of rapid scientific development in Europe, écorchés became compulsory tools in artistic training.

Previously, they were considered more like art chamber pieces (much like the human skull at that time) with an added dimension of memento mori, the reminder of everyone’s unavoidable death. Along with antique book collections, an écorché was an additional symbol of an educated person – you would occasionally see one in their studies.

Neoclassicism influences

The 18th and 19th centuries was a time of Neoclassicism, the movement in the arts that drew its inspiration from the Classical art and culture of Ancient Greece and Rome. The aesthetical depiction was as significant as anatomical precision, with compositions often becoming idealized or even canonical.

It was a rather complex task to render the correct anatomy and at the same time not to be too naturalistic and lose the aesthetic dimension.

What sets Caudron's écorché apart?

A large proportion of the known écorchés was made between the 16th century and the beginning of the 18th century. Back then they were rarely used as tools for anatomy studies.

The écorchés of this period mostly delivered an artistic experience, and their creators did not engage in medical consultations beforehand. Thus, these sculptures often lacked detailed development of the figure’s muscles and muscle tension.

It was a rather complex task to render the correct anatomy and at the same time not to be too naturalistic and lose the aesthetic dimension.

Three P.P. Caproni & Bro. casters with a reproduction of Houdon’s écorché.

Neoclassicism influences

This changed in the latter part of the 18th century with the works of Jean-Antoine Houdon and Johann Martin Fischer who created the first life-size écorchés. Houdon and Fischer participated in cadaver dissections, where they could examine the human muscular system up close.

They were then able to convincingly depict its distinctive parts in their artwork. Just like their predecessors, they constructed their figures with an aesthetic ideal in mind, but it was done so skillfully that the anatomy became believable as well.

The écorché of Saint John the Baptist

Houdon’s écorché sculpture, standing in contrapposto with its right arm outstretched, was an anatomical study he created for himself while preparing to work on a marble sculpture of Saint John the Baptist.

Later his friends and colleagues recognized it as valuable in its own right and suggested that he made a mold of the écorché to produce copies. Houdon’s anatomical study became widely popular, and he gave many copies of the écorché to art academies and schools. It is still one of the most recognized écorchés among artists.

Yet the nature of its popularity is somewhat accidental. Is the canonical posture of Houdon’s neoclassical Saint John the Baptist the best écorché from which to learn the form of the muscles?

Left: A bronze of the Borghese Gladiator, Italy first half of the 17th century.

Right: The original Borghese Gladiator by Agasias of Ephesus, 100 BC.

The first écorché comissioned by a physician

The 19th century saw an increasingly active collaboration between artists and doctors, which was a game-changer for écorché design. It was then when a physician Antoine Louis-Julien Fau commissioned and oversaw the creation of Jacques-Eugène Caudron’s L’écorché combattant.

After carefully examining numerous muscle men, including those by Houdon and Fischer, Fau concluded that they had numerous anatomical defects. His ambition was to create an anatomically accurate écorché. Indeed, Caudron’s sculpture achieves both – excellent anatomical precision as well as an aesthetic sculptural composition

The unique posture of L'écorché combattant

In the sculpture, the man appears to be taking a step onto his right foot and has his left arm raised above him, hand flexed. His right arm has been brought back and hand clenched in a fist.

The template for the posture of L’écorché combattant is a bronze sculpture by an unknown Italian artist from the 17th century. The bronze is, in turn, a modified version of the Borghese Gladiator by Agasias of Ephesus.

Interior of the anatomical collection of the Dresden Art College with a life-sized Caudron’s L’écorché combattant visible on the right side of the picture.

The unique posture and the great anatomical precision of Caudron’s L’écorché combattant make it a great aid in anatomy studies for artists. It is all there –flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, supination, pronation, etc. Even the figure’s torso is in motion, with one of its sides bent and the other one extended. That is why we decided to make it into a digital 3D model.

Watch our video series about écorchés to learn more!

In the first video, Uldis Zarins explains how écorchés sit somewhere between art and medicine. During the Renaissance, the first écorchés were used mostly by artists, but later they also became increasingly popular among medical students.

Join our newsletter

Be the first to receive news about upcoming books, projects, events and discounts!