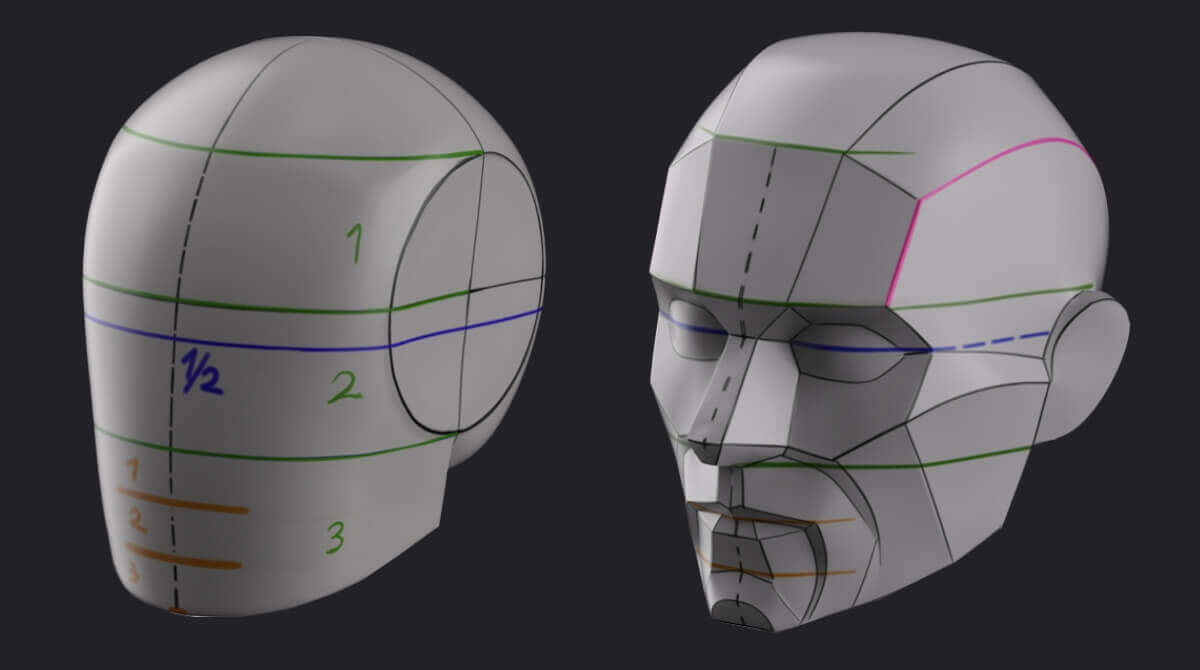

Forming the Head: Simple to Complex

Form the head by starting with simple shapes and gradually add structure and detail. We cover base forms like the helmethead and egghead, first- and second-level blockouts, and the anatomy and variation that shape the head.